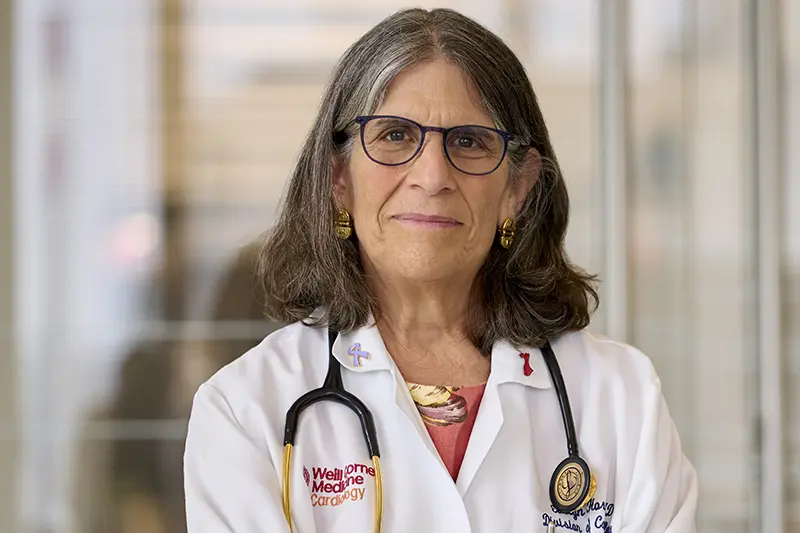

Over the course of nearly four decades as a cardiologist, Dr. Evelyn Horn has been on the forefront of innovation in heart failure.

In 1992, she helped establish the first heart failure program in the country dedicated to caring for pre-transplant and heart failure patients and advancing clinical heart failure research at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia. At various points in her career there, she oversaw clinical services and the heart failure fellowship program, expanded the adult pulmonary hypertension program, and incorporated pulmonary vascular disease into the division. In 2007, she moved to NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine to become the Director of Heart Failure and Pulmonary Hypertension at the Perkin Center for Heart Failure. The program she created offers innovative, comprehensive treatment for advanced heart failure and pulmonary hypertension.

Along the way, Dr. Horn earned the moniker of the “Right Heart Doctor” because, as she says, “I was one of the few heart failure doctors who was knowledgeable of not only the left side of the heart but also the right — a direct consequence of having a significant focus on pulmonary hypertension,” she says. This meant colleagues would often seek her expertise on some of the toughest cases that involved right heart failure. “I’ve always tried to provide hope when others couldn’t.”

Dr. Horn spoke with NYP Advances about her early experiences helping build heart failure as a key subspecialty within cardiology and where she sees the field going next.

When did you know that you wanted to specialize in cardiology?

I did look into other specialties before choosing cardiology. At one point I had considered pediatric surgery, and when I applied for residency programs I simultaneously applied to obstetrics and gynecology and internal medicine. But my colleagues in medical school always said I was going to go into cardiology. There was something about the pathophysiology of cardiovascular conditions and my mathematical approach to reasoning that blended well together, so even after exploring other things I came back to cardiology. I was aware that I was picking a field with very few women in it, but I was well-prepared. I went to Stuyvesant High School in New York City the first year it went co-ed. I was one of 13 young women admitted.

I always maintained an interest in high-risk obstetrics throughout my career. During my medical school obstetrics rotation, I helped manage a patient with advanced mitral stenosis through the end of pregnancy and delivery, and I continue to have an interest in the cardiovascular complications of pregnancy and the crossover between hypertensive heart disease, peripartum cardiomyopathy, and preeclampsia.