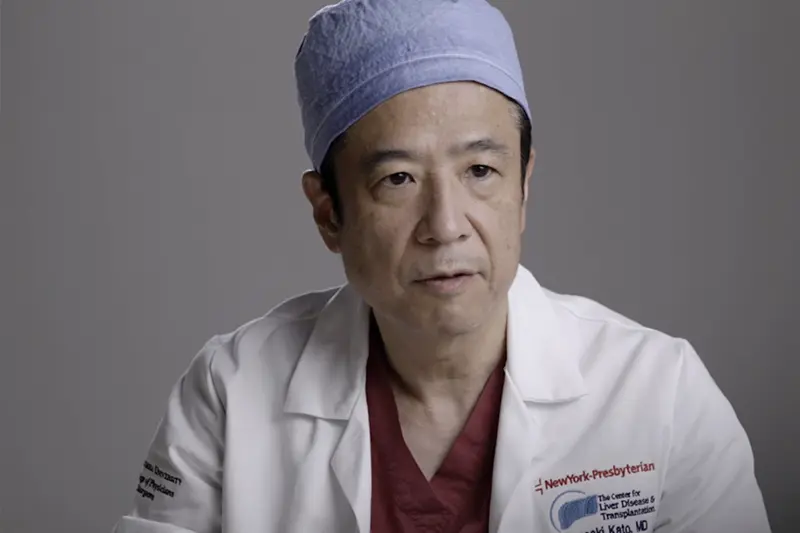

Resiliency and focus are the trademarks of Dr. Tomoaki Kato, a world-renowned multiorgan transplant surgeon who regularly takes on difficult surgeries that often require marathon hours in the operating room.

The Chief of the Division of Abdominal Organ Transplantation at NewYork-Presbyterian/

When tackling cases other doctors might find daunting, Dr. Kato’s motto is: “Don’t say ‘no’ just because it’s never been done before,” he says. “I always try to see if there’s anything we can do outside the box to help a patient in need.”

Dr. Kato spoke with NYP Advances about how innovation and pushing boundaries in the name of patient care has shaped his career.

How did you know that you wanted to pursue transplant surgery?

While I was finishing my surgical residency in Japan, I knew I wanted to do advanced training in the U.S. in a specialty that wasn’t as readily available in Japan. Although Japanese surgery is also advanced, there were two areas that were lacking back then: vascular surgery, because there was really no atherosclerotic disease then in Japan; and transplant surgery, because the diagnosis of brain death wasn’t accepted in Japan at the time, so organ donations weren’t prevalent.

I went to the vascular surgery professor first for a recommendation, but he was too busy preparing for a talk at an international conference, so he told me to come back in a month. Instead, I went to the transplant professor, and he wrote me the recommendation right away. If the vascular professor had been available at the time, it’s possible I could have become a vascular surgeon.

You’ve since become a leader in multiple-organ transplantation. What drives you to continue expanding the boundaries of transplantation?

It always comes down to the patient. A lot of the hard cases I’ve taken on are because they’ve gotten a “no” from someone else. I think it’s meaningful to at least try to find a solution because it’s likely that it exists, you just have to find it through outside-the-box thinking.

I saw it as modifying the technology and the knowledge we already had to do whatever we could to help the patient.