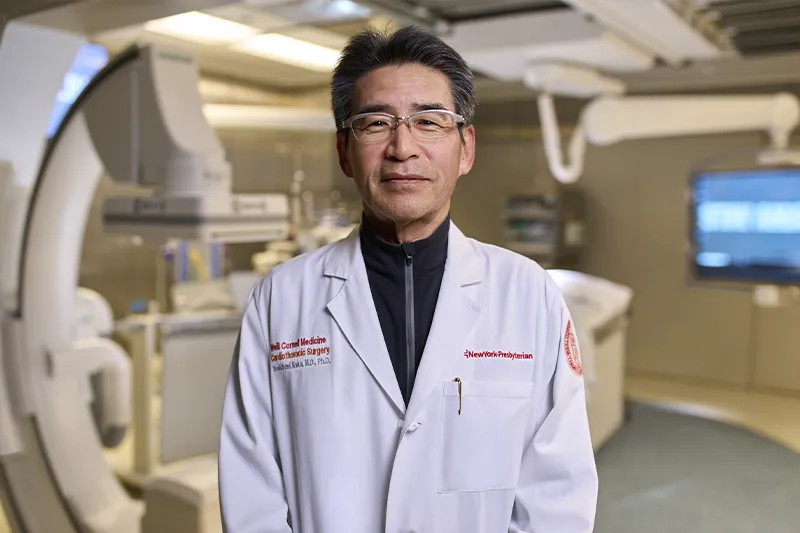

For nearly three decades, Dr. Yoshifumi Naka has been treating some of the sickest heart patients at NewYork-Presbyterian. He started his career at Columbia in 1993 as a research fellow but stayed on to become a clinical fellow in cardiothoracic surgery and left ventricular assist devices (LVADs), a technology that was then in its infancy.

Since then, Dr. Naka, Surgical Director of Heart Failure, Heart Transplantation, and Mechanical Circulatory Support Programs at NewYork-Presbyterian, has helped build the heart failure program at NewYork-Presbyterian as a transplant surgeon and pioneer in mechanical assist support devices. He helped lead clinical trials at Columbia that tested multiple generations of LVAD technology and in 2011, led the team that performed the first total artificial heart implant in the New York City area. In recent years he helped expand NewYork-Presbyterian’s heart transplantation and heart failure program to Weill Cornell Medicine, performing the first heart transplant at the NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center campus in 2023.

“The clinical scenarios we work with are challenging, but we want to work on the hardest cases to try and save these patients,” says Dr. Naka. “That’s why we’ve always been focused on trying new therapies and technologies.”

Dr. Naka spoke to NYP Advances to share how he’s seen his field evolve over the decades, where he hopes it goes next, and why he sees training the next generation of surgeons as the most important part of his job.

When did you know you wanted to pursue cardiothoracic surgery with a focus in transplantation?

My first year of medical school at Osaka University, I met the chief of cardiothoracic surgery, who was one of the pioneer cardiac surgeons in Japan. I admired him and wanted to be like him, so became interested in cardiac surgery early on. I was in a program where I went straight into getting my PhD after medical school and doing a year of residency. I received training in different kinds of surgery during residency, but during my Ph.D. program I was interested in studying immunology, which led me to do my research in transplantation biology. All my interests came together in heart transplantation.

I came to Columbia as a postdoc research fellow where I studied endothelial biology and ischemia-reperfusion of the organs after transplantation. After doing three years of research, I wanted to stay in the United States to continue my medical training, and the mentors and friends I made here encouraged me to stay on for a clinical fellowship in cardiothoracic surgery at Columbia.

You’ve been involved with LVAD technology since its early stages. How have you seen it evolve, and where would you like to see it go next?

Doing surgery with the first generation of devices was tough because the equipment was big and the patients were very sick; the surgeries were almost always done as emergency surgery rather than urgent or elective. LVADs were only a bridge to transplant then, and I would usually do a patient’s LVAD surgery as well as their heart transplant once a donor heart became available. Around 2004, at Columbia we participated in the clinical trials of the second generation, which helped it get FDA approval. The device was much smaller, with a driveline going through the abdominal wall and connected to the controller and battery, and became much more durable. I performed the surgery for one of the first patients to ever exchange their first generation LVAD for the second generation, and they were able to live 11 or 12 more years on the newer device.

Now we’re on the third generation, which is much more sophisticated and presents fewer complications. I really pushed to enroll a lot of patients in the clinical trial for it, and as a result Columbia became the number one enrollment site, which was a big accomplishment because this was such a large, nationwide study. One of the biggest complications with previous models, device thrombosis, was almost eliminated with this model; survival rates were also much higher, and the risk for stroke was greatly reduced. But there is still a driveline to a controller outside, so I would love to see the technology evolve to the point where everything is contained inside the body.

Looking back on your career, is there a particular achievement that stands out to you?

I don’t really view my greatest accomplishment as a paper I’ve written or a trial I was a part of. My best accomplishment is that I’ve trained many surgeons. Every year as part of our Advanced Heart Failure and Transplant Cardiac Surgery fellowship at Columbia, we train one or two fellows in heart failure surgery as well as residents who want to learn this subspecialty. I work with them on every heart failure case, especially LVAD or artificial heart surgeries, and much of the time I let them take the lead while I assist, instructing them on every step.

To become an outstanding surgeon, I believe you also have to be a good teacher, both in terms of teaching technique and the science behind it.