Dealing with Death and Dying in the ICU

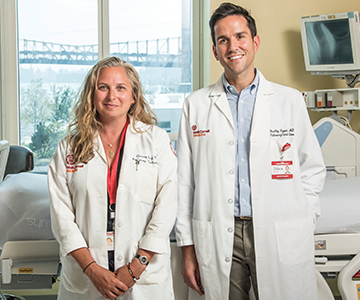

Dr. Lindsay Lief and Dr. Bradley Hayward

In the medical ICU, pulmonary medicine and critical care physicians are often faced with the death of their patient. While trained to save the lives of the critically ill, these physicians must also have the skills and knowledge to provide palliative care to the patient and emotional support for the family when end of life is inevitable. At NewYork-Presbyterian/

Educational Support for Clinicians

After joining the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at Weill Cornell, Dr. Hayward sought to share his insights and knowledge with critical care fellows. “I wanted to work with the fellows about end-of-life care, how to approach it and do it right because even though they are focused on saving lives, the reality is that about 20 percent of their patients die. I wanted to help educate them about how to assist in that process and make it less difficult for the patients and families.”

Noting that pulmonary and critical care fellows receive little, if any, formalized palliative care education, he approached the Division of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine to develop a case-based curriculum that would teach such skills as communication, leading family meetings, and managing symptoms of dying patients.

“We met once a month over the course of the year,” says Dr. Hayward. “The first half of the lecture was didactic and teaching, the second part was letting the fellows debrief about the process. We’ve received a lot of positive feedback, as they felt that they needed to learn more about end-of-life care because it’s something they confront on a daily basis.”

“From a doctor’s standpoint, we tend to think of end of life as a failure,” continues Dr. Hayward. “I’ve been trying to change that thinking and that palliative care really is part of our job as critical care physicians. It’s the right thing to do from a human standpoint.”

The program has since expanded to include both fellows and all internal medical residents who rotate through the MICU.

Dr. Hayward stresses the importance of being direct with the family if the patient is actually dying. “I will tell them that I think that the patient is dying, rather than couching it in euphemisms or saying they are just not getting better. We have to confront the fact that dying is an aspect of our jobs, and like any other part of our job, we have to handle it and we have to do it well. The fellows need to know what happens in the dying process – how to manage symptoms and how to manage pain. We give them the skills and tools to do that.”

Dr. Hayward believes it is important for the physicians to share their experiences in the ICU when a patient is dying. “At the end of our sessions we encourage them to talk about their own emotions and personal feelings. When family members ask difficult questions, I want them to know what they can say. When someone is crying and telling you that life is unfair, what do you say in that situation?”

Dr. Hayward also finds teachable moments in the ICU. “The other day a young man was dying, and before the resident went into his room, I said, ‘His wife is going to ask you if he is dying and what should she do? What are you going to say to her?’ The resident was stunned and unable to express what she was feeling. I wanted to help her to think about how to answer that question.”

“There are some parts of communication where you can learn to be a more effective communicator,” says Dr. Hayward. “While every situation is unique, you can learn how to frame conversations to deal with highly charged emotions and still guide the conversation to a useful end rather than letting the emotions overcome the situation.”

Dr. Hayward is currently preparing a study with pre- andpost-surveys from participants to evaluate the effectiveness of the curriculum. “Initially the field of critical care wasn’t as receptive to palliative care as a specialty,” he says. “Now I think we are realizing the power in it and that there are skills that can help us make the situation better for the patients, families, and for ourselves as doctors.”

Studies Underway to Improve End of Life

After completing residency and fellowship training in pulmonary and critical care medicine at Weill Cornell, Lindsay Lief, MD, joined the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. Also acknowledging the relatively high mortality in the medical ICU, Dr. Lief, now Medical Director of the MICU, working with colleagues in the Weill Cornell Center for Research on End-of-Life Care under the direction of Holly G. Prigerson, PhD, has undertaken several clinical trials to improve end-of-life care in the ICU.

“The data will tell you that patients prefer to die at home,” says Dr. Lief. “However, in the United States a quarter of people die in the hospital and many in the ICU. For some people, it’s an acute event that we were trying to prevent. For others, it is just the end of their life. We want to help make their death as peaceful and comfortable and with as much dignity as possible.”

In the recently completed SOS (severity of suffering) study, the researchers surveyed ICU nurses of patients who had died. “Ideally you would be able to survey a patient and say, ‘How bad is your pain from 1 to 10? How bad is your nausea from 1 to 10?’ But our patients are likely delirious, sedated, unresponsive, intubated, unable to phonate, and/or too weak to write. If we were to do that study, we’d have a very selective population that would not accurately represent the diversity of patients who die in the ICU.”

According to Dr. Lief, nurses have been shown to be excellent surrogates for assessing patients and rating their symptoms and overall quality of death. “Through chart extraction we determined what interventions the patients received at end of life,” explains Dr. Lief. “We then correlated their perceived suffering with interventions that were done with feeding tubes, dialysis, and ventilators, as well as DNR and withdrawal of care, to get a sense of what symptoms contribute most to suffering and loss of dignity. From our clinical experience, we hypothesized that pain was not the most prominent symptom. We found that other symptoms are as burdensome, including swelling, shortness of breath, being restrained, and weakness.”

This study led to another investigation that is evaluating patients on ventilators or any form of respiratory support. “Our SOS studies told us that shortness of breath is a big problem, so we are surveying patients if they are able to communicate, as well as bedside nurses and any family members or loved ones in the room to get a sense if dyspnea is being assessed accurately,” says Dr. Lief.

One recently validated measure of dyspnea in patients in hospice, notes Dr. Lief, includes well-known signs of respiratory distress, such as patients using accessory muscles for breathing and flaring their nostrils. “This measure seems to have some reliability in the hospice setting, but it has never been looked at in patients who are on mechanical ventilation in the ICU,” says Dr. Lief.

In another study supported by the NIH and National Cancer Institute, the Weill Cornell researchers are addressing the needs of family members of patients who die in the ICU. “Many studies of surviving loved ones and caregivers show that they have more post-traumatic stress disorder and prolonged grief than people whose loved ones die at home,” says Dr. Lief. “How can we mitigate that? Does a condolence card from the doctor help? It turns out it does not. Does a palliative care intervention specifically with the caregiver help? It does not according to the single study that has looked at it. So, through this funding we are providing family members of sick patients in the ICU with four brief interventions with a psychologist to prevent PTSD by helping them to remain present despite the difficulty of the situation, and then following up with them after the patient passes.”

“The essence of our research,” adds Dr. Lief, “is to provide symptom relief for our patients – many of whom are at the end of life – and to help their families get through this most arduous time.”

Reference Article

Su A, Lief L, Berlin D, Cooper Z, Ouyang D, Holmes J, Maciejewski R, Maciejewski PK, Prigerson HG. Beyond pain: Nurses’ assessment of patient suffering, dignity, and dying in the intensive care unit. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2018 Jun;55(6):1591-98.e1.