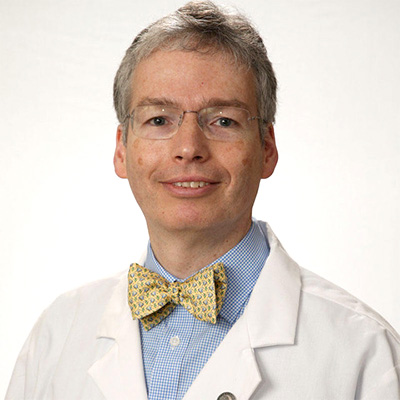

In the middle of a muddy pasture on a farm in New Jersey, Dr. David Slotwiner, an electrophysiologist and chief of cardiology at NewYork-Presbyterian Queens, calls out to his border collie, Cosmo. He shouts commands like “lie down” and “come by” to get Cosmo to stop, start, and change directions. Their goal: to corral a small herd of sheep into a pen.

This is a typical weekend for Dr. Slotwiner, who is also an assistant professor of clinical medicine and population health sciences at Weill Cornell Medicine. Sheepherding became an unlikely side passion after he began these visits to the farm to help Cosmo, his family’s border collie, whose aggressive, reactive nature was proving problematic.

Both Dr. Slotwiner and his wife, Anne, who have always had dogs in the family, suffered multiple bites as Cosmo grew older. “We were encouraged to give him up, but there was no way we were going to do that because he would have been put to sleep,” he says. Determined to help Cosmo, they consulted multiple dog trainers, to no avail. Then, one of them referred the couple to a farm that trained border collies to herd. On their first visit, almost immediately after seeing the sheep, “Cosmo understood how his presence could influence them,” Dr. Slotwiner says. “Within 45 seconds, he was herding them. His personality changed; we realized this gave him a lot of confidence and mental stimulation. It was like he found his calling in life.”

Dr. Slotwiner also became hooked and started to train as a handler. He says his journey with Cosmo has been a test of his communication skills, patience, resilience, and ability to problem-solve — which isn’t so different from what’s required of him on the job, whether he’s leading global efforts in his field to standardize patient data or teaching trainees in the operating room.

“Whatever leadership role I am in, the parallels are quite remarkable,” Dr. Slotwiner says. “It’s always a constant adjustment trying to be as effective of a leader as I can.”

Dr. Slotwiner spends his weekends practicing herding on a sheep farm with his two border collies, Cosmo and Luna (pictured in video).