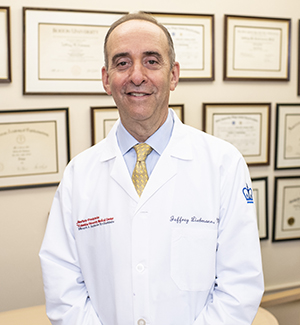

Ophthalmology was one of the first specialties to investigate artificial intelligence in clinical application, largely because of the amount of visual data that is collected in the diagnosis of eye diseases — and NewYork-Presbyterian and Columbia’s high patient volume and unique collaboration between clinicians and scientists has helped the institution remain at the forefront of AI research in the field, explains Jeffrey Liebmann, M.D., director of the glaucoma service at NewYork-Presbyterian and Columbia and vice chair of the Department of Ophthalmology at Columbia.

“Ophthalmology is a very imaging-driven and data-driven field. We’ve accumulated very large databases here, some of which contain data on hundreds of thousands of visual field tests and optical coherence tomography images collected over many years. We know this is critical for AI,” Dr. Liebmann says. “Over time, we’ve been able to apply algorithms to this data, which has evolved into machine learning and artificial intelligence. Our strong academic partnerships are helping us advance and develop this technology into ways to assist clinicians in practice.”

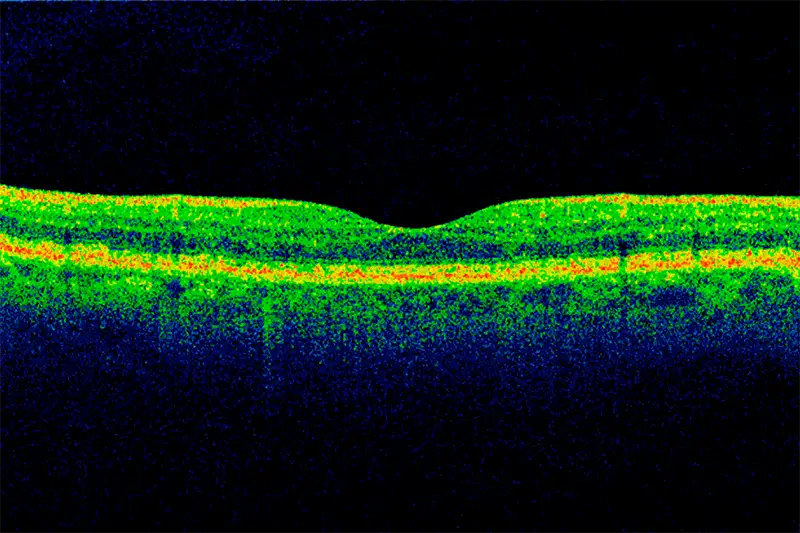

Optical coherence tomography scan of a section through the macula of the retina. The volume of high-quality imagery that is collected in ophthalmology provides rich data for AI models.

These partnerships were fortified in 2022 with the launch of the Artificial Intelligence for Vision Science (AI4VS) Lab under the direction of Kaveri Thakoor, Ph.D., assistant professor of ophthalmic science in the Department of Ophthalmology at Columbia, who has a research team composed of computer science and biomedical engineering students. Dr. Thakoor has partnered on approximately 15 projects with ophthalmologists since the lab’s inception that range from expediting the detection or severity of ophthalmic diseases to using gaze-tracking to improve medical training.

Dr. Thakoor says the lab’s work is focused on developing AI tools that fall under one of three principles: robustness, interpretability, and portability. Robustness refers to accurate and generalizable algorithms that can be applied to data collected from anywhere. Interpretability means those algorithms need to be trusted and valid in a clinical setting, which is why the lab always partners with a clinical expert. Finally, portability ensures that the AI tool is broadly accessible on high- and low-cost devices and across proprietary platforms.

“Our projects all start with a clinical question that a physician wants to solve,” says Dr. Thakoor. “I see AI as having the potential to be a teammate to clinicians, almost acting like a second opinion from a colleague or a corroboration on a complicated case.”

I see AI as having the potential to be a teammate to clinicians, almost acting like a second opinion or a corroboration on a complicated case.

— Dr. Kaveri Thakoor

Using AI to Identify Thyroid Eye Disease

Many of the lab’s projects revolve around deep learning to improve diagnostics using data gathered from biomedical imaging. One such project is focused on AI-assisted screening for thyroid eye disease, an autoimmune disorder that affects the tissues and muscles of the orbit, and in severe cases can lead to disfigurement or blindness.

However, there isn’t a great understanding among general practitioners, endocrinologists, or other referring physicians of the signs or symptoms of thyroid eye disease, which can lead to either inaccurate diagnoses or delays in diagnosis, says Lora Dagi Glass, M.D., an oculoplastic surgeon and division director of ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery in the Department of Ophthalmology at NewYork-Presbyterian and Columbia.

“It can be a bit haphazard who gets referred to me. Sometimes it is people who have obvious signs, but other times it’s patients who have just received a diagnosis of thyroid disease, even though there isn’t a specific concern for the eye,” says Dr. Glass, noting that thyroid disease and thyroid eye disease are not always linked. “Other times, patients have had thyroid eye disease for months and could have come to me a lot earlier. So, I thought it would be interesting to figure out a way to create a screening app based purely on a photograph of the eye that can help a referring physician determine who should actually be referred for a proper in-person exam.”

Federated learning gives us a resource that allows us to use data without sharing private information. There is strength in numbers while also maintaining confidentiality.

— Dr. Lora Dagi Glass

Dr. Glass has been working with Dr. Thakoor and her lab for the past year to build an anonymized database of simple, forward-facing digital external photographs taken from age- and gender-matched control patients and patients with a confirmed diagnosis of thyroid eye disease. They are also working with additional academic centers to leverage a federated learning approach, which means that each site keeps their data local rather than in a shared central database and trains the AI models on their local data. The mathematical information from each site is then aggregated and standardized to common data model conventions.

“Federated learning gives us a resource that allows us to use all that data without sharing private information. There is strength in numbers while also maintaining confidentiality and hopefully rising to the challenge of creating a model that is also highly ethical,” Dr. Glass says.

The first few models have been completed, and next steps are to add more academic centers to join the federated learning consortium and then trial the AI model prior to app development. Portability is one of the main goals of this project, so although the app would initially be used by practitioners, Dr. Thakoor sees a future where people could use their own smartphone photos to potentially detect thyroid eye disease.

“Our eventual vision is that it’s so broadly accessible that someone could take an image of their face, and we can incorporate that into our models training,” Dr. Thakoor says.

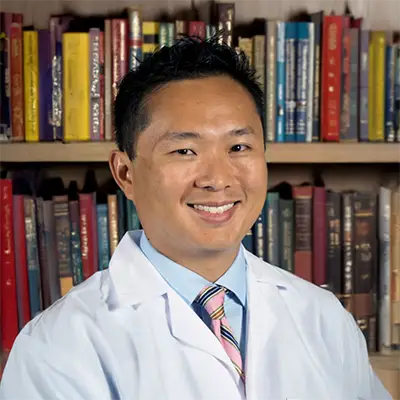

AI-Assisted Training for the Next Generation of Ophthalmologists

Using artificial intelligence to advance the diagnosis of disease is happening beyond the patient level; AI is also innovating how residents and fellows learn. “AI has exploded in the last few years, so wearing my education hat, I thought about how we could harness it to educate our trainees,” says Royce Chen, M.D., vice chair of education and residency director for the Department of Ophthalmology at NewYork-Presbyterian and Columbia. “They still need to be trained in all the fundamental ways to become excellent ophthalmologists, but it’s clear that technology has changed our practice over the last 20 years.”

Dr. Chen has been working with the AI4VS Lab since 2022 to help residents and fellows improve their imaging interpretation using data collected through gaze-tracking technology. They are tracking and measuring the eye movements of both experienced ophthalmologists and trainees to see where they look at an image to make a diagnosis. The experienced physicians’ gaze data is used to improve vision transformer architectures by adding information on where the experts look first and areas where their gaze stays longer.

We know in the beginning diagnosis takes longer for a trainee, but if we can teach them to become faster and more accurate, they’re better able to deliver optimal care.

— Dr. Royce Chen

“Our trainees evaluate roughly 1,500 to 2,000 images a year, which they have to quickly make decisions on. We’re basically teaching the artificial intelligence model how the expert does it,” explains Dr. Chen. “For example, where does an expert look to make a diagnosis of macular degeneration, versus what a novice does? How do you know if something is a macular hole? We know in the beginning diagnosis takes longer for a trainee, but if we can teach them to become faster and more accurate with each diagnosis, they’re better able to deliver optimal care to patients.”

Ultimately, Dr. Chen wants to build a database of labeled pathology, which will be part expert-driven and part AI-driven, that can be used to accelerate the learning process for trainees. “I imagine that pretty soon, the AI will get good enough that they can automatically label the new images that come in to assist both trainees and seasoned clinicians in the diagnostic process,” he says. “It’s going to fundamentally change our field.”

Looking Ahead: Expanding Multidisciplinary Use of AI Diagnostics

As the use cases for artificial intelligence expand, Dr. Thakoor believes the ability to detect systemic disease through the eye opens the doors to cross-specialty collaborations. “The eye is like an open book of microvasculature that can clue you into cardiovascular disease, neurologic disease, or diseases of the endocrine system, such as diabetes,” she says. “By using AI plus biomarkers that are uniquely detected in the eye, we can create a first line of defense for whole body health and hopefully help patients get the care they may not know they needed sooner.”

The interdisciplinary relationships that exist among the broader clinical and academic community at NewYork-Presbyterian and Columbia provide a ripe environment to fulfill this vision. “Being able to collaborate with multiple people within our department, across the medical school and across the university is unique,” Dr. Thakoor adds. “On a daily basis, I speak with not only our medical colleagues but also my engineering colleagues, my computer science colleagues. I think it is what has allowed us to stay at the forefront of technical innovation.”