A team of investigators from Weill Cornell Medicine, Stanford Medicine, and University of California San Diego School of Medicine are studying new ways to combat depression and create models that can predict which treatment is likely to work for individual patients. Their efforts are supported by a three-year grant funded by Wellcome Leap, an organization that provides resources that target global human health challenges. The contract is part of a $50 million Wellcome Leap program, Multi-Channel Psych: Revealing Mechanisms of Anhedonia that aims to accelerate new treatment options for depression, which, according to the World Health Organization, affects an estimated 280 million people worldwide.

Dr. Conor Liston

“The purpose of this project is to develop new approaches to treating depression that work more effectively and in a more personalized way,” says principal investigator Conor M. Liston, PhD, MD, a neuroscientist and psychiatrist in the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute and the Department of Psychiatry at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. “This is one of the central goals of work in my lab, so this is a great opportunity to advance our efforts in this area.”

In collaboration with Dr. Nolan Williams at Stanford University and Dr. Jeff Daskalakis at University of California, San Diego, Dr. Liston’s research team is focusing on the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), the FDA-cleared noninvasive therapy that involves short bursts of magnetic energy to alter the activity of nerve cells in the brain. TMS can be used alone or in tandem with antidepressant medications and is typically reserved for patients with treatment-resistant depression. “TMS requires patients to come to the clinic daily, and medications do not,” he says. “So, for many people, medications are a good first treatment to try, but TMS is a great option for people who do not respond to medications or experience unacceptable side effects.”

Patients across the three study sites will receive various treatments that include different types of TMS or escitalopram (Lexapro), one of the most commonly used first-line treatments for depression and representative of the larger class of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Patient responses are evaluated through clinical assessments and brain scans with the ultimate goal of developing algorithms that can match individual patients with personalized treatment plans.

“Personalized strategies would enable physicians to match treatments to the individual patients who are most likely to benefit from them and hopefully achieve faster, more effective outcomes.” – Dr. Conor Liston

Building on Groundbreaking Research

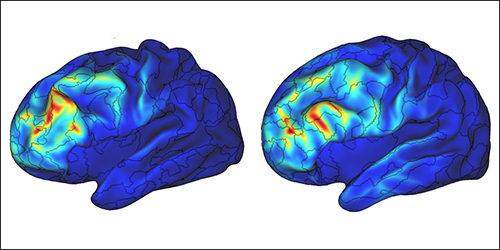

“Many people stand to benefit from TMS yet very few people are being treated with it,” says Dr. Liston, who is a pioneer in the field. In 2019, he established the Interventional Psychiatry Program in the Department of Psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine. Now directed by Dr. Benjamin Zebley, the Interventional Psychiatry Program is founded on the work of Dr. Liston and his colleagues in developing a novel approach to TMS that calls on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) for individual brain mapping. It is known through studies in both animal models and humans that emotional states are encoded in complex neural network activity patterns and that directly changing these patterns via brain stimulation can shift mood. The mapping determines the specific circuits of the brain most affected in an individual patient’s depression and then uses this information to guide the application of TMS.

TMS uses functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) for individual brain mapping

“Our research has shown that there are at least four distinct patterns of abnormal brain connectivity in patients with depression, and those abnormalities are associated with different kinds of symptoms,” says Dr. Liston. “Symptom variations are complicated. One subtype had high levels of anxiety and low levels of anhedonia, and conversely, another subtype had high levels of anhedonia and low levels of anxiety. Both are considered depression, though exhibit quite differently. Understanding this led to our second question: What does this mean for TMS? How do subtypes of depression influence a patient’s likelihood of responding to treatment?”

According to Dr. Liston, many psychiatric disorders are driven by dysfunction in particular brain networks. “The more that is understood about the specific circuits involved, the more we can use this flexibility to aim the TMS magnet to the area we want to target to treat the disorder in question.”

Testing fMRI-Guided TMS

Prior to the awarding of the current Wellcome Leap grant, Dr. Liston, Dr. Faith Gunning, and their colleagues had previously initiated a clinical trial at Weill Cornell Medicine that is testing whether fMRI can be used to guide TMS and improve its efficacy. “Unlike medication, with TMS we can pinpoint the intervention in a way that antidepressant medications – which ‘bathe’ the entire brain – cannot,” adds Dr. Liston.

The clinical trial, which is currently in the recruitment phase and expected to run through 2026, seeks to enroll over 300 patients who will be randomized to receive repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) targeting the dorsomedial or dorsolateral prefrontal cortices (dmPFC or dlPFC) and guided by the fMRI treatment over a 6-week period. In the Wellcome Leap-funded project, the team will be testing an accelerated form of rTMS, involving 10 sessions per day hourly for 5 days.

The primary goal is to determine if accelerated rTMS treatment will yield rapid improvement in symptoms for patients with depression in just 5 days, and to develop fMRI biomarkers for predicting response. These fMRI biomarkers could be used to personalize the treatment by predicting who will benefit from TMS, determining the optimal treatment target, and improving treatment outcomes. Patients will undergo a clinical assessment of symptoms and an fMRI brain scan before and after each treatment course to measure its effect on symptom severity and on fMRI measures of functional connectivity. A similar study is under way for patients with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

“In our earlier research, we found that the different subtypes of depression were associated with different likelihoods of responding to transcranial magnetic stimulation,” says Dr. Liston. “Like many of our antidepressants, TMS works for some people and not for others. To be able to predict whether this treatment would work for a patient beforehand is significant and would enable us to develop more personalized strategies.”