Celiac disease can cause metabolic bone disease (MBD), most commonly osteoporosis, and an increased risk of fracture, but the relationship between the two diseases is not completely understood. To bridge the information gap between celiac disease and MBD, NewYork-Presbyterian/

“Although celiac disease has been studied for a long time, there is still so much we don’t know about celiac disease and metabolic bone disease,” says Dr. Walker, who is board-certified in internal medicine and endocrinology and is an International Society for Clinical Densitometry Certified Clinical Densitometrist. “To begin with, we don’t fully understand the pathophysiology and mechanisms underlying what causes bone loss and the increased risk of fractures in celiac disease patients, and we don’t have consensus regarding when celiac patients should be tested for osteoporosis or when patients should be treated with osteoporosis medications. More large-scale, epidemiological research would give us the answers we need to better council our patients and improve patient care.”

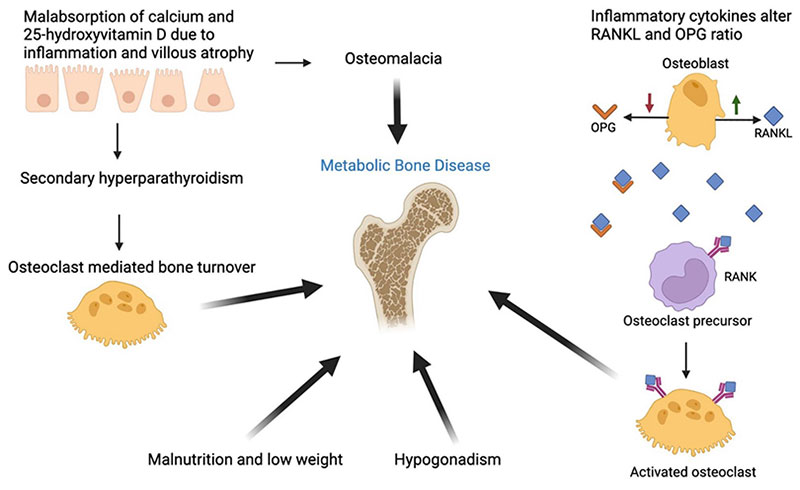

Schematic of potential pathophysiological mechanisms contributing to metabolic bone disease in celiac disease (reproduced from Kondapalli, A. V., & Walker, M. D. (2022). Celiac disease and bone. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab., 66(5), 756-764).

In their review, the authors explain celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder that causes inflammation in the small intestine triggered by eating foods that contain gluten (proteins found in wheat, rye, and barley) in individuals with a genetic predisposition to the disease. Although the genes (HLA-DQ2/HLA-DQ8) associated with celiac disease are present in up to 30-40% of the general population, only a minority of people present with symptoms of celiac disease (1-3%), suggesting that additional factors contribute to the manifestation of disease.

An interplay of at least four factors may contribute to the development of bone disease in celiac disease:

- the malabsorption of calcium and vitamin D leading to secondary hyperparathyroidism and increased skeletal break down

- pro-inflammatory cytokines favoring development of cells that break down bone, known as osteoclasts

- hypogonadism

- low weight and malnutrition

“Malabsorption of calcium and vitamin D is the cornerstone of MBD in celiac disease,” says Dr. Kondapalli. “We also know that different inflammatory cytokines can cause bone breakdown in other conditions, but we don’t know how much this is at play in celiac disease. More research on the subject would illuminate the interconnections between these processes and help us determine the most effective approach to screening and treatment.”

Beyond the classic gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms of celiac disease, a common expression of the condition is MBD, which leads to an increased risk of fracture in patients with celiac disease. Studies show that patients with celiac disease, including those without GI symptoms, have lower bone mineral density compared to controls. The prevalence of osteopenia or osteoporosis in newly diagnosed celiac disease patients ranges from 38-72%.

This wide range underscores the need for more definitive data, says Dr. Walker. “We don’t know the actual prevalence of osteoporosis in celiac disease patients, because we don’t yet have information based on good epidemiologic samples,” says Dr. Walker. This information may influence guidelines regarding DXA screening for patients with celiac disease. “Most studies of the prevalence of osteoporosis in celiac patients are based on data collected from patients who present at specialized centers, which may treat those with the most severe celiac disease. At Columbia, we collected data from a large cohort of patients with celiac disease that found 44% of adults over the age of 50 have osteoporosis.

“Although the guidelines suggest screening for MBD overall, we still need research to know who and when to screen: Should we screen all celiac patients at diagnosis, or after the patient has been on a gluten-free diet? Should we screen everyone -- men, women and children?” says Dr. Kondapalli. “Another important goal is to increase awareness among providers of the need to screen celiac disease patients at high risk for osteoporosis,” adds Dr. Kondapalli.

There is also uncertainty regarding screening for celiac disease in those with osteoporosis. “There is limited data about when to screen people with osteoporosis or bone fractures for celiac disease , especially if they have no GI symptoms,” explains Dr. Walker, who sees patients in the Metabolic Bone Disease Center at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia. “The decision to screen patients for celiac disease depends on patient factors. It is important to consider in those who have lost bone density or had fractures while being treated for osteoporosis or young patients with osteoporosis or multiple fractures, such as premenopausal woman and men under age 70 as well as those with persistent vitamin D deficiency despite treatment”.”

Dr. Walker works closely with physicians at the Celiac Disease Center at NewYork-Presbyterian/

Men with celiac disease seem to be particularly susceptible to osteoporosis, but limited data exist that explains why this is so. One possible reason is that men come to presentation later than women, so the disease is identified and treated later in the process.

— Dr. Kondapalli

One area of growing interest for the researchers is osteoporosis in men with celiac disease. Although celiac disease is more common in women than in men, our study showed that men with celiac disease had osteoporosis more frequently than women with celiac disease. “This was a surprising result. Men with celiac disease seem to be vulnerable to osteoporosis, but limited data exist that explain why this is so,” explains Dr. Kondapalli. “One possible reason is that men come to presentation later than women, so the disease is identified and treated later in the process.”

In a current study, Dr. Walker and Dr. Kondapalli are exploring the bone health of men with celiac disease. “The study is assessing skeletal microstructure using high-resolution peripheral quantitative CT, an imaging technique which provides 3D images of the bone, along with biochemical and inflammatory markers,” explains Dr. Kondapalli. “This will help elucidate the pathophysiological processes leading to bone loss in men with celiac disease.”

Few studies have assessed which celiac disease patients have the greatest increase in BMD after beginning a gluten-free diet. This information is critically important for us to know which of our CD patients are most likely to improve with dietary changes alone and which need earlier treatment with prescription therapy for osteoporosis so we can counsel and monitor them appropriately.

— Dr. Walker

Another compelling realm of inquiry is the impact of a gluten-free diet, the mainstay treatment for celiac disease, on bone disease in celiac patients. “While we do see improvement in bone mineral density among patients who follow a gluten-free diet, there is great inter-patient variability and increased fracture risk can persist,” says Dr. Walker. “Few studies have assessed which celiac patients have the greatest increase in bone mineral density after beginning a gluten-free diet. This information is critically important for us to know which of our celiac disease patients are most likely to improve with dietary changes alone and who may need earlier treatment with prescription therapy for osteoporosis in addition to dietary changes so we can counsel and monitor them appropriately.”

“Patients have so many good questions. They ask me, ‘Are my bones going to get better on a gluten-free diet alone? Can I start a gluten-free diet now and then try treatment later, or should I treat my osteoporosis with prescription therapy right away?’ We don’t necessarily have definitive data to answer these questions with ideal certainty.”

“We also don’t have specific data about how celiac disease patients respond to prescription osteoporosis treatment,” adds Dr. Walker. “We extrapolate from data obtained in the general population and use treatments approved for postmenopausal or age-related osteoporosis,” Dr. Walker adds.

With multiple areas of investigation identified, the authors believe future studies will help develop standardized guidelines for the screening and treatment of bone disease in patients with celiac disease, enabling them to live longer, more healthy lives.

“More research will help us better counsel patients. For instance, it would be great to have an answer for each patient when they ask about gluten-free diet and treatment. Not every celiac patient with osteoporosis on a gluten-free diet will need osteoporosis treatment, but some ultimately will,” Dr. Walker adds.