Pathways to Diabetes Prevention: It’s All Relative

Dr. Magdalena M. Bogun

In 2015, Magdalena M. Bogun, MD, an endocrinologist in the Naomi Berrie Diabetes Center at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, was one of four physicians selected to participate in the TrialNet Emerging Leaders Program designed to promote the engagement of new investigators in diabetes clinical research. Dr. Bogun focused her research on the natural history of type 1 diabetes drawing on data from TrialNet, an international network of leading academic institutions, physicians, scientists, and healthcare teams that conduct investigations on the study, prevention, and early treatment of type 1 diabetes (T1D).

“My investigation was a longitudinal study of insulin secretion in patients who have had metabolic testing both before and after diagnosis of T1D,” says Dr. Bogun. “We found that insulin production decreases long before a patient is actually diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. Now that we know that a reduction in insulin production begins earlier on, we can diagnose T1D earlier in patients with antibody screening. So the question became how do we reach these individuals.”

The Genetic Connection

Columbia is participating in the NIH TrialNet Pathway to Prevention, which offers free screenings at more than 200 TrialNet locations to relatives of people with T1D to evaluate their personal risk of developing the disease. This unique screening can identify the early stages of T1D years before any symptoms appear. Research has shown that relatives of individuals with T1D are 15 times more likely to develop the disease than the general population. The increased risk is linked to the presence of five diabetes-related autoantibodies. Based on the TrialNet data, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, American Diabetes Association, and the Endocrine Society now classify having two or more of these autoantibodies as early stage T1D.

“Our goal is to see which of these patients’ relatives will actually develop diabetes,” says Dr. Bogun. “People who screen positive for two or more diabetes-related autoantibodies are almost 100 percent likely to develop diabetes in their lifetime. The problem is that we don’t know when — three, five, or 10 years in the future.”

The criteria for testing include individuals between the ages of one and 45 who have an immediate family member with T1D, and those between the ages of one and 20 who have an extended family member with T1D.

The screening involves a blood test for the presence of diabetes-related biochemical autoantibodies (GAD 65, IA-2A, mIAA ICA, and ZnT8A). A positive antibody test is an early indication that damage to insulin-secreting cells may have begun. “Those who have at least two positive antibodies are given an oral glucose tolerance test, and then we test their glucose levels two hours later,” says Dr. Bogun. “Essentially, it is like a stress test to diagnose type 1 diabetes sooner. If autoantibodies are present, participants are invited to be monitored with an oral glucose tolerance test every six months to detect high sugar levels and clinical onset of T1D.”

The Treatment Challenge

As per the current ADA guidelines, if an individual has an onset of clinical symptoms, HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, 2-hr plasma glucose (PG) ≥ 200 mg/dL during an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), or fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL2, the person would be classified as having stage 3 type 1 diabetes. “Because we are diagnosing type 1 diabetes so much earlier than in the past and not waiting until the patients exhibit symptoms, we are now faced with a scenario of how to treat them. My current research is trying to determine what is being advised and what is the best way to treat these patients who are being diagnosed much sooner,” says Dr. Bogun. “Are they being told to check glucose levels and wait until they increase to treat? Does the provider start insulin right away? Right now, there is no standardized approach; it’s patient-specific.”

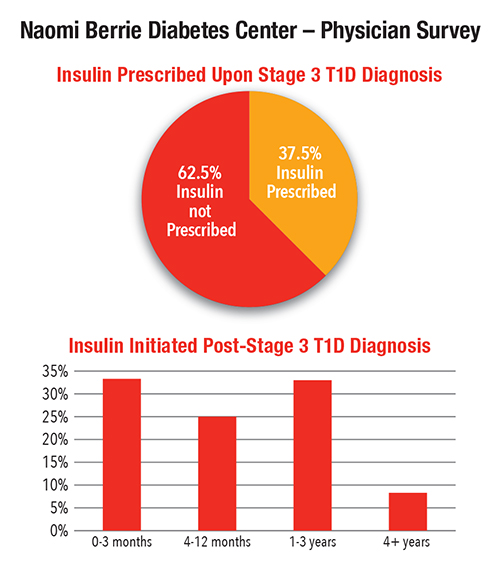

“We wanted to better understand how patients at our site who were diagnosed with new onset

- 37.5 percent were prescribed insulin upon diagnosis

- 44 percent were prescribed basal insulin

- 33 percent were prescribed rapid-acting insulin

- 22 percent were prescribed both basal and rapid-acting insulin

The survey additionally indicated that 55 percent of patients who were not prescribed insulin were asked to monitor glucose levels daily; 9 percent were asked to monitor weekly; and 36 percent before meals.

“The time between diagnosis and initiation of insulin treatment varied — nearly 60 percent of patients were prescribed insulin within a year of stage 3 T1D diagnosis,” says Dr. Bogun. “Less than 10 percent of patients did not require insulin treatment more than four years after T1D diagnosis. “We plan to expand this study to all TrialNet centers to evaluate how various treatment options at diagnosis impact patient outcomes.”

Dr. Bogun has a message for clinicians about screening for type 1 diabetes. “I would strongly suggest that they have the relatives of their patients with type 1 diabetes screened through Pathway to Prevention — especially the children,” she says. “When children are diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, they actually have less insulin-producing cells than adults who are diagnosed and they might get sicker. If we can identify those patients earlier they can receive the treatment they need earlier. And if they do not require treatment yet, we can give them the education necessary on how to test glucose levels and how to detect high blood sugar much earlier than what would otherwise be detected in the community.”

Reference Article

Julie Behrend (Indiana University School of Medicine), Magdalena Bogun, Sarah Pollak, Robin Goland. Naomi Berrie Diabetes Center. Management of Asymptomatic Patients Diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes Through Pathway to Prevention in TrialNet. Poster Presentation. 10th Annual NIDDK Medical Student Research Symposium. 2018.

Related Publications