Only a decade ago, the therapeutic possibilities provided by CRISPR-based gene editing technologies seemed like a thing of the distant future. However, with the FDA approval in 2023 of a CRISPR/Cas9 gene therapy for the treatment of sickle cell disease, what was once confined to the laboratory is now being advanced through clinical trials with the potential to transform patients’ lives across a wide swath of diseases.

Since 2013, Stephen Tsang, M.D., Ph.D., an ophthalmic geneticist in the Applied Genetics Clinic in the Department of Ophthalmology at NewYork-Presbyterian and Columbia and director of the Jonas Children’s Vision Center Laboratory, has been advancing CRISPR and other gene-editing strategies for retinal degenerative disorders. His commitment to genome engineering traces back to his training in the National Institutes of Health-National Institute of General Medical Sciences Medical Scientist Training Program at Columbia, where he completed his Ph.D. under renowned molecular virologist Dr. Stephen P. Goff. Along with developmental biologist Dr. Elizabeth J. Robertson, Dr. Goff pioneered the demonstration that stem cells carrying engineered mutations could contribute to all tissues of the adult mouse, including germ cells, enabling transmission of those mutations to future generations.

“The technology developed at Columbia demonstrated the first successful application of genome engineering with germline transmission in a mammalian gene,” notes Dr. Tsang, who is also the László Z. Bitó Professor of Ophthalmology, Pathology and Cell Biology at Columbia and a member of the Columbia Stem Cell Initiative. “It was one of the earliest forms of genome engineering B.C. — before CRISPR — and the campus’s groundbreaking work inspired me.”

After residency, Dr. Tsang returned to NewYork-Presbyterian and Columbia in 2005 to capitalize on the institution’s strengths in genome engineering and clinical gene therapy, launching a laboratory focused on stem-cell and therapeutic editing for neurodegenerative disorders such as retinitis pigmentosa (RP), a leading inherited cause of blindness. Although gene therapy has shown promise for RP, the disorder’s genetic heterogeneity — there are thousands of causative variants across more than 80 genes — complicates treatment. “CRISPR offers the best hope for restoring retinal function regardless of an individual’s genetic profile,” he says.

Dr. Tsang launched his lab at Columbia to focus on genome engineering and CRISPR approaches to reprogramming metabolome in the retina to promote cell survival.

RP’s sheer genetic heterogeneity limits one-gene-at-a-time solutions. To address this, Dr. Tsang’s team developed an “ablate-and-replace” strategy: an in-vivo CRISPR system that excises the mutant rhodopsin (RHO) allele and delivers a functional replacement to restore vision. By using two guide RNAs instead of one, they increased the likelihood of precisely removing the defective gene sequence; adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors then delivered the replacement gene. This design demonstrates CRISPR’s potential not only for dominant RP but also for other dominant disorders.

“We called it genome surgery,” says Dr. Tsang. “Unlike conventional gene therapy, which is focused on gene supplementation — where you give someone a gene to treat a condition, using it to act like medication — we were doing surgery on a chromosome to fix or repair that gene. So far, CRISPR is the closest thing to a curative, one-time treatment that we can provide to treat different inherited disorders.”

Using CRISPR to Rejuvenate the Eye’s Glycolic Metabolome

Some of Dr. Tsang’s more recent research uses CRISPR technology to tackle retinitis pigmentosa at another level. Although each of the 80-plus genes tied to RP triggers the disease in different ways, one commonality is that blindness usually occurs because the light-sensing neurons experience anabolic biosynthetic failure and become deprived of energy. In essence, most of the mutations leading to RP cause neurons in the eye to starve themselves.

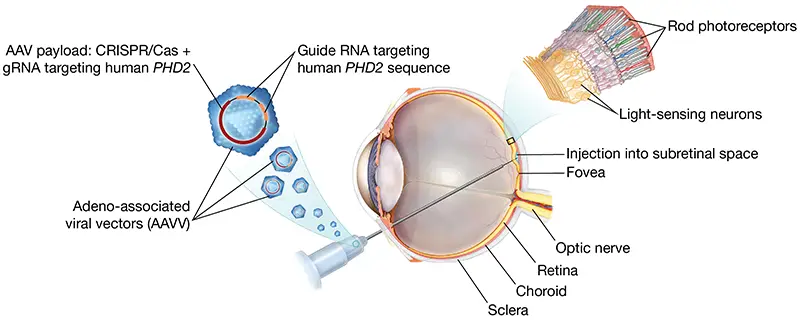

To address this, Dr. Tsang and his team designed a CRISPR system delivered via AAV to edit the PHD2 gene, which is involved in glycolysis in the light-sensing rod cells of the retina. When injected into the eyes of mice genetically engineered to develop RP, the treatment decelerated progression of the disease by about a month, which is equivalent to approximately 10 years in a human lifespan. The results from this study were published in Cell Reports Medicine in 2024.

An adeno-associated viral vector carrying CRISPR/Cas and a guide RNA targeting the human PHD2 sequence (AAV::PHD2_gRNA) is delivered into the subretinal space via a posterior pars-plana approach, forming a localized retinal bleb over the photoreceptors.

“A universal precision metabolome rejuvenation would be a vast improvement over the limited options now available to most RP patients, which do little to prevent blindness,” says Dr. Tsang. “Our results showed that reprogramming metabolism can play an important role in the treatment of neurodegenerations. Because our therapy specifically targets mutant photoreceptors, with more research this strategy may provide a safer and effective treatment for retinal disorders caused by an array of genetic deficiencies.”

Having demonstrated the potential of CRISPR in pre-clinical mouse models, Dr. Tsang is looking to further test these in-vivo techniques in clinical trials to bring this potentially game-changing therapy to patients. One of the current challenges is that most trials are focused on ex-vivo CRISPR techniques, where the patient’s cells are removed and engineered outside of the body, then returned to the patient. Dr. Tsang sees a lot of promise in in-vivo treatments because they may not only help improve the economics of administering CRISPR, but they also allow for a quicker and more tolerable recovery, with patients potentially returning home same day.

“CRISPR represents the ultimate implementation of precision medicine,” says Dr. Tsang. “It has shown effectiveness for both recessive and dominant disorders, which means that as CRISPR therapeutics become more widely available, virtually any mutation could be precisely targeted for treatment.”

Despite the field’s challenges for in vivo, Dr. Tsang notes that the tight integration of clinical care and research at NewYork-Presbyterian and Columbia creates an ideal engine for gene-therapy innovation. “We’ve been here since the early days of genome engineering, and our laboratory and Ph.D. students are eager to apply ever-evolving CRISPR technologies. NewYork-Presbyterian thrives at the convergence of science and patient care, allowing us to practice the future of medicine already.”

The investigational vector AAV::PHD2_gRNA has been designated by the FDA under reference number DRU-2022-9199.