|

||||||||||||||||||||

Depression in Later Life: Improving Access and Adherence to Treatment While major depression is not a normal part of the aging process, there is a strong likelihood of it occurring when other physical conditions are present. According to Mental Health America, more than two million of the 34 million Americans age 65 and older suffer from some form of depression. Studies have shown that the majority of elderly patients experiencing major depression remain inadequately treated due to a complex combination of patient, clinician, and systems-driven barriers. At NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, Patrick J. Raue, PhD, and Jo Anne Sirey, PhD, are working on better ways to identify older adults with depression, reduce barriers to care, and help ensure adherence to their treatment of choice. A Shared Decision-Making Intervention for Depression “Research has shown that depression is quite common, particularly in primary care and other community settings where medical illness, disability, and social isolation are prevalent,” says Dr. Raue, Associate Professor of Psychology in Psychiatry, who conducts research at the Institute of Geriatric Psychiatry of the Department of Psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine. Dr. Raue extends his expertise to creating partnerships and conducting research in medical and community settings, and developing and implementing depression care management and other interventions to address the mental health of older adults. Between 2009 and 2014, supported by an NIMH R01 grant, Dr. Raue and his colleagues focused part of their research on testing a shared decision-making (SDM) intervention for elderly depressed patients in primary care settings. “This model is based on a patient-centered view of health care, and it is in reaction to more traditional, paternalistic medical approaches where the physician knows best,” says Dr. Raue. “With shared decision-making, the patient’s role is elevated in the care process and he or she is treated as an equal partner in treatment decisions.” In this collaboration, explains Dr. Raue, clinicians are responsible for presenting patients with information about depression and treatment options, and patients are encouraged to let their physicians know about their previous treatment experiences, what their preferences and goals are, and how they would like to be treated. “These are non-demented primary care patients who meet criteria for clinically significant depression,” says Dr. Raue. Study goals were two-fold: to increase patient adherence to the treatment of choice and to reduce depression symptoms. The approach involves a half-hour shared decision-making intervention with selected patients delivered by a trained nurse, while the comparison group was managed by a physician who identified depression, treating it as he or she deemed appropriate. “My hypothesis was that patients who participated in the SDM intervention and received education about depression would be more likely to pursue some type of depression treatment, whether that be medication, psychotherapy, or both,” says Dr. Raue. “Because patients are involved in the decision, they are more likely to see treatment as appealing and something they will follow through on.” The SDM intervention included two follow-up telephone calls by the nurse at one and two weeks to determine if the patient was still pleased with their treatment decision and if progress had been made in pursuing that treatment, whether it be filling the prescription or making an appointment for psychotherapy. “We believe that SDM is powerful enough to make a difference, to get people to not only start treatment, but also to stay in treatment and begin to recover from depression,” says Dr. Raue. “This approach may be used as a stand-alone intervention to help older patients formulate and successfully implement treatment decisions. Alternatively, it may also be blended into standard care management approaches so as to maximize their impact.” Facilitating Access to Mental Health Services “Much of my work is trying to identify both the need of older adults for mental health services and helping them utilize services,” says Dr. Sirey, Associate Professor of Psychology in Clinical Psychiatry, who conducts research in the Institute of Geriatric Psychiatry of the Department of Psychiatry of Weill Cornell Medicine. As Principal Investigator of two R01 grants funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, Dr. Sirey has developed and implemented interventions to increase the use of mental health services among depressed older adults living in the community and an intervention to improve treatment adherence among elders in primary care settings. In addition, her research has documented the negative impact of stigma on participation in treatment. Dr. Sirey’s work in facilitating access to care involves a number of projects that integrate screening and detection of psychological difficulties and providing brief psychotherapies. As one example, she and Dr. Raue are working with a grant from the Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation to integrate depression and anxiety screening and psychotherapy into the Elderly Crime Victims Resource Center within the New York City Department for the Aging that provides services to older adults who are victims of crime or elder abuse. “We have been screening depression in elder abuse victims and have found that 30 percent of them screened positive for depression, the highest rate of depression symptoms seen in any of the aging service providers,” says Dr. Sirey. After Super Storm Sandy, Dr. Sirey received a $1.4 million grant from FEMA to help assess older adults who were impacted by the storm and provide them with brief psychotherapy. The Sandy Mobilization, Assessment, Referral and Treatment of Mental Health (SMART-MH) program is a collaboration with the Aging in New York Fund affiliated with the New York City Department of Aging. The SMART-MH program targets adults aged 60 and older living in New York City flood zones. “These are individuals who wouldn’t normally seek out mental health services so we were going out to them to determine if they had a need for these services,” says Dr. Sirey. “It combines community partnership with outreach, needs assessments, and where applicable, clinical evaluation, as well as providing aging services and mental health treatment referrals.” Dr. Sirey continues this work, also supported by a grant from the Samuels Foundation, to ensure the sustainability of the SMART-MH program. Improving Adherence to Antidepressants In some of her earlier research, Dr. Sirey demonstrated that older adults in treatment who report concerns about stigma are more likely to drop out of treatment and more likely to be non-adherent. “Though it was a small sample, it really put stigma and the impact of stigma on everybody’s radar,” says Dr. Sirey. “More recently, with a collaborator in the University of Michigan, we documented the fact that older adults who are African-American are more likely to be non-adherent when they’re getting antidepressant medication for depression than Caucasian older adults. We looked at individuals who are already in treatment and found that Caucasian women have the highest rate of adherence and African-American women have the lowest rate of adherence.” With this and other evidence in hand, Dr. Sirey has since developed, with funding from the National Institute of Mental Health, an intervention to improve adherence to antidepressant medications. “Individuals who are prescribed an antidepressant first must reconcile their beliefs about what’s wrong with them, what will make a difference, the social context in which they live, and the cost and benefits of treatment,” says Dr. Sirey. “Our adherence intervention personalizes the treatment. We determine the patient’s concerns about treatment and barriers to adherence. Sometimes those barriers are logistical: ‘I can’t keep track of my medications; I have difficulty refilling my prescriptions; I take multiple medications.’ Sometimes they are psychological: ‘I’m worried that people will think I’m crazy; I’m worried that if I am depressed I will lose my independence or be excluded from social interactions.’ We try to understand those personal concerns; these are often concerns the patient doesn’t tell their physician.” The interventions are brief, involving one-on-one meetings, where they meet with the older adult, talk to them about the barriers, and then shift the conversation to asking what they would get out of life if they felt better, encouraging the patient to form a goal. “Older adults who come into treatment tell us ‘I would like to enjoy my time with my grandchildren more. I’d like to be more interested in going out and socializing with my friends.’ So now we have the cost of depression and they define the benefit. Collaboratively we build a plan that makes sense for their lives and help them implement it. Sometimes it is very concrete: ‘I’ll put my medication by my coffee maker so when I get up in the morning I’ll remember to take it.’ Sometimes it is more subtle: ‘I am not going to share with my daughter-in-law that I’m taking an antidepressant because of how she will react.’ This all takes place in three very brief, very focused sessions. What we are really talking about is helping people acclimate to the world of depression treatment.”

A New Way of Thinking About Schizophrenia For more than 20 years, Daniel C. Javitt, MD, PhD, Director of the Division of Experimental Therapeutics and Professor of Psychiatry and Neuroscience at Columbia University Medical Center, has been building an alternative conceptual approach for schizophrenia that withdraws from the one-size-fits-all antipsychotic treatment options traditionally given to patients since the 1950s. Schizophrenia was first described over a century ago, and for the past 60 years compounds developed based on dopamine models that focus on controlling hyperactivity and hallucinations, such as chlorpromazine, haloperidol, risperidone, or olanzapine, have remained the only FDA-approved treatments for schizophrenia. Dr. Javitt, who is also the Director of Schizophrenia Research at the Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, is using neuro-physiological methods and functional brain imaging to investigate the role of N-methyl-D-asparate (NMDA) receptors in sensory processes and compare the contributions of sensory dysfunctions in attention, perception, social cognition, and reading to impairments in higher-level processes in schizophrenia. NMDA receptors are “responsible for forming new connections and rehearsing old skills,” and are among several types of receptors for the neurotransmitter glutamate – the primary neurotransmitter for balancing mood in the brain. “There is no medication to improve cognition, yet cognition is the most important part of the disease in terms of predicting outcome of quality of life,” says Dr. Javitt. “This is an entirely new way of thinking about schizophrenia. It is exciting to be at Columbia because here we have the right tools for the intersection of cognitive neuroscience and psychiatry. The new model transmitter system is changing the way we think about the experience and thoughts of the individuals with symptoms. And this leads to new treatments.” An early symptom, he explains, includes losing the ability to read fluently. “If you don’t have the right model of the disease, you don’t think about it. If you don’t think about it, you don’t test it. If you don’t test it, you don’t find it,” Dr. Javitt says, emphasizing the importance of asking a patient exhibiting symptoms to read aloud and gauging their ability to pronounce words at their previously held reading level. “Those regions of the brain actually degenerate; we were able to find that many people lose four school grades worth of reading ability. “Individuals also lose the ability to pick up intonation and inflection,” continues Dr. Javitt. “They don’t detect when people are being sarcastic, and they don’t detect the emotion in their voices and on their faces. If they are not able to understand the social cues, it leads them to withdraw from the social scene, which, in turn, feeds into paranoia.”

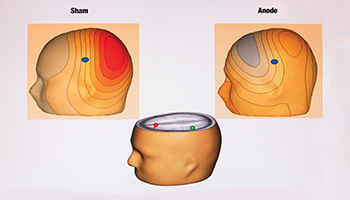

In addition to exploring what is needed for treatment at the basic cognitive level, Dr. Javitt’s most recent research investigates the role of brain oscillations in cognition, and on the ability of brain stimulation techniques, such as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), to modulate normal and abnormal brain activity by stimulating and inhibiting regions and remapping its functions. “Noninvasive brain stimulation has the power to remodel and resculpt the brain, and only treat the necessary areas,” says Dr. Javitt, who supports a multipronged team-based approach to managing schizophrenia. Researchers in the brain stimulation program of the Division of Experimental Therapeutics also conduct studies using multiple modalities. In addition to tDCS, these include deep brain stimulation, transcranial magnetic stimulation, magnetic seizure therapy, and electroconvulsive therapy. In describing the difference between these stimulation modalities, Dr. Javitt explains tDCS is meant specifically for rebuilding deficient activity. These research and treatment options, he emphasizes having recently discovered unexpected crossover, have vast opportunities for overlap with depression, bipolar disorder, cancer, Parkinson’s disease and more. “Paradoxically, one of the most immediate benefits to emerge from the glutamate story on schizophrenia is its role in depression,” notes Dr. Javitt. “In schizophrenia, you want to stimulate the NMDA receptors and restore plasticity, but in depression it turns out that blocking NMDA receptors is useful for patients who don’t respond to the traditional antidepressants. In fact, it has had dramatic effects on depressive symptoms. So instead of stimulating glutamate, we’re antagonizing glutamate to treat depression instead of schizophrenia. The ultimate target may not always be where you thought it was, but more importantly, we are understanding new ways to interact with and manipulate the brain,” says Dr. Javitt. “It is learning behaviors, unlearning behaviors, and tweaking brain circuits with personalized approaches.”

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||